Making nucleus colonies for new hives

/Hives at Front Porch Farm in Healdsburg have just finished pollinating the plums and are ready for peaches and apples.

Its been a busy spring here in Northern California, where my first nectar flow began the last week of January when the plums began to open their white and pink buds. With the fresh nectar and plenty of pollen from the willows, acacias and bays, my hives are all thriving. Last week I worked up in Healdsburg at the Front Porch Farm, a sweet farm nestled in a valley with the Russian River as its north east border.

I’ve been busy managing my colonies for spring to prevent swarming. I’ve also been raising the next batches of spring queens to split my colonies the last week of March. I’ll use these colonies to add to my own apiaries and will sell the extra nucs to my hobbyist clients. It feels good to know that I can be a part of resilience for myself and my community by supporting farms and producing products for local markets.

I’ve had the most productive spring, with the production hives in some of my locations having such a strong nectar flow that they’re building new comb and capping the entire super in a week to 10 days. That’s a rate of about 50 pounds of honey per week, and it lasted three weeks before the weather changed and things got back to a normal spring cycle for the area. I spend most days outside, in the sun, a smile on my face and surrounded by bees. It just doesn’t get any better than that.

We’ve harvested four supers of honey, and four deeps of bees and brood from these colonies in 2 weeks.

Not only am I harvesting honey at a much faster rate than ever before, but I’ve been building up big healthy colonies to raise the next season’s young queens. I’m set to have a bumper crop of starter colonies for sale. But first, I need to raise more queens.

How do I raise queens? In a nutshell, when a hive is queenless, they automatically shift their focus to produce queen cells. Lots of them, and whichever queen hatches out first kills the other queens and gets to be the new queen of the hive. I use this natural tendency to raise many queens, with larvae selected from my best hives, and rather than letting the first one win, I let every queen hatch in her own small mating box with her own retinue of bees. The mating boxes are small- about 1/8 the size of a normal hive- just big enough to support a young queen while she hatches and goes out on her mating flights. Each box has a different color and so do the lids, so queens can recognize their own hives and not accidentally show up at the wrong door.

Prepping mating boxes

Each mating box has 4 mini frames, a cup or two of bees, plus a queen cell to get started. Here I have the boxes set out, ready to receive bees.

Mating boxes at my apiary on Quail Ridge.

The queen hatches in her mating box and spends about a week getting ready to fly. Once she’s ready, she may seek mates for several days and may mate with as many as 20 drones. Then she settles down and spends the rest of her time laying eggs and being tended by her daughters. These hives are from two batches a week apart, with a total of 38 queens. In the foreground is the swarm box and a cup I use to add bees to hives that are a little skinny.

How do I make so many queen cells?

I graft queens from the larvae of my best colonies, those that are gentle, produce lots of honey, and demonstrate resistance or tolerance for varroa mites and their associated pathogens. Each 1-day old larvae is gently scooped out of normal worker brood comb and placed in an artificial queen cup. Those artificial queen cups are added into a hive that is queenless and filled with nurse bees eager to have a job to do.

Grafting larvae. On a side note, 1 day old larvae are too small for my camera to capture, so this is actually too old for a good graft!

QUeen cells are tended by nurse bees, who feed each QUeen Larvae 160 times a day

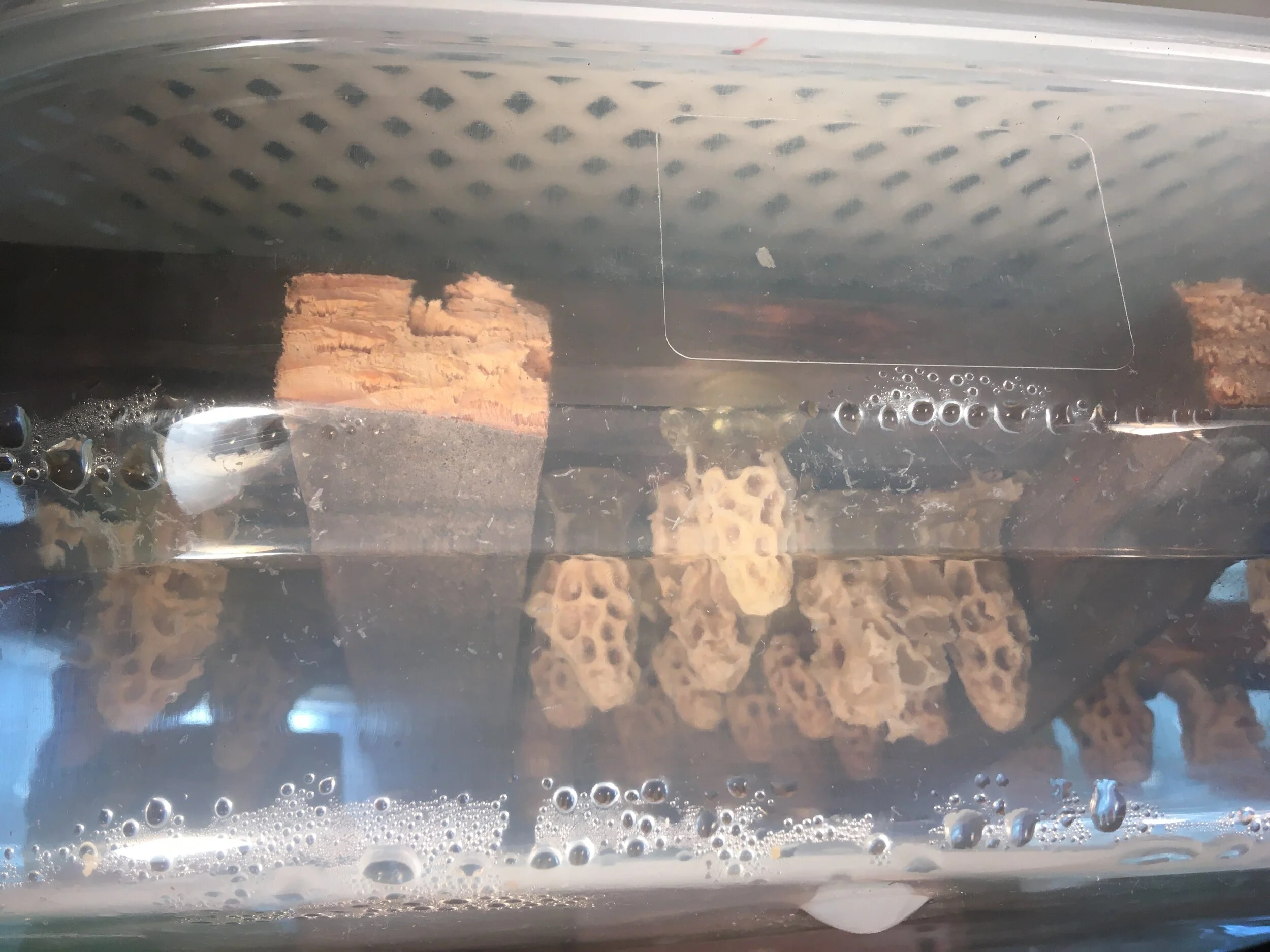

Some queens hatch out in an incubator, which allows me to evaluate each queen for fitness before she goes into a mating box

You can see from the image above that each queen cell starts from a plastic cup and looks like a peanut when its ready to hatch. This is basically a cocoon, complete with spun silk. This method of grafting queens allows me to save every queen instead of letting the one who hatches first win out over the others. In the incubator without bees, the queens won’t kill one another. This gives me time to evaluate each queen and to make only the number of mating boxes I need for the queens who make the cut.

2020 QUeens will have a blue dot on their backs to identify their age and make them easier to spot

Once queens have started laying, they will be moved into nucleus colonies with full-sized frames. This is a 5-frame medium nuc, with 2 nucs in one hive box, divided in the center. This method allows the nucleus colonies to stay nice and warm, sharing heat between the two halves. While queens are in the double-nucs I evaluate each, checking out how well they are laying, before sending them out to start new hives.

Each nuc is transported in a cardboard nuc box to its new home.